Undertone

by Hope Madden

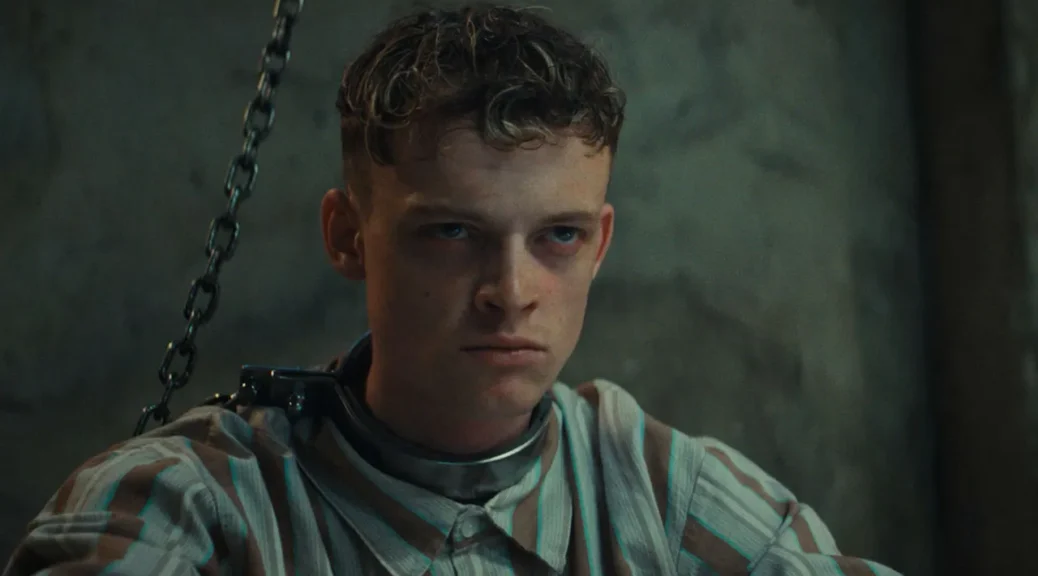

Ian Tuason’s paranormal podcast feature Undertone offers a lot of reasons to be impressed. It’s a single location shoot, and almost a one-hander. Aside from a catatonic mother (Michéle Duquet) and a variety of voices, Nina Kiri is on her own.

Kiri plays Evy, who is recording her paranormal podcast Undertone from her dying mother’s house. Evy’s been staying at Mom’s for a while now, and if she’s honest about it, she’d like it to just be over with. Evy’s waiting for the death rattle.

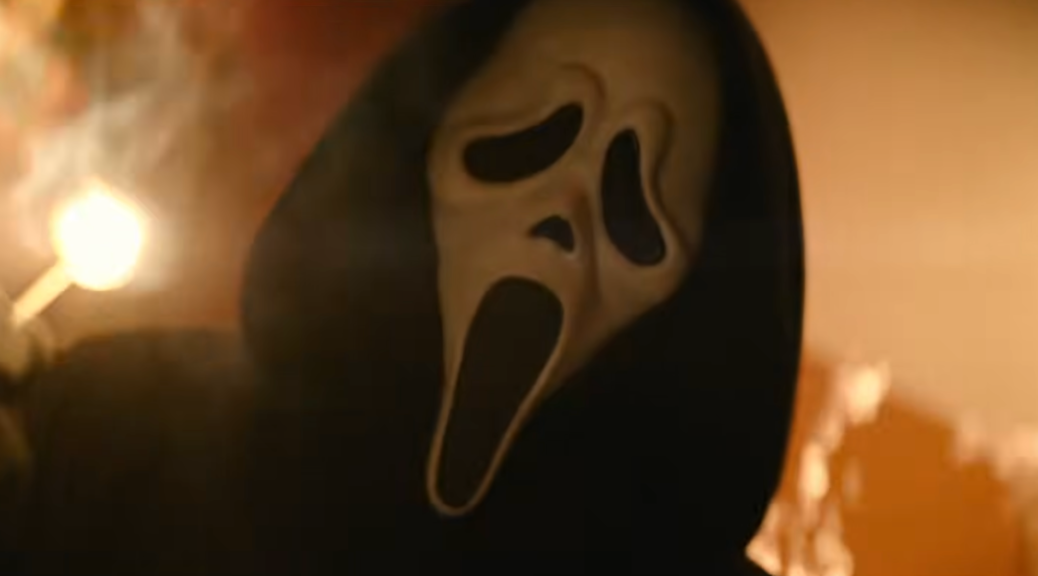

She loves Mama, but the relationship is thorny with Catholic guilt and shame. We sense this more than see it as Tuason crowds his set design with Catholic iconography. It’s a busy if impressive set, and Tuason makes great use of it with fascinating camera work. He uses mainly stationary cameras, often set off-angle so they feel more like a voyeur’s or ghost’s point of view, or even a security camera. The movement reinforces that sense. On the rare occasion that the camera does move, it does so in an obviously mechanical way that even more closely resembles security footage.

This gives the film a Paranormal Activity vibe—fitting, as Tuason is slated to write and direct the next installment in the found footage franchise.

But Undertone is less about what you see and more about what you hear. The somewhat oppressive sound design is intentional, of course, and frequently effective.

Kiri delivers a heroic performance. Not only has she no conscious actor to react to, but the vast majority of her performance is simply Evy, in headphones, listening to something.

The film falls apart at the story level. Evy and her podcast co-host Justin (voiced by Adam DiMarco) decide to listen to a set of 10 audio files emailed to them anonymously. The files conjure up something supernatural that, combined with Evy’s isolated, spooky, guilt-laden environment, starts affecting her headspace.

But the sound files and podcast are silly. The mythology within the house—Evy’s relationship with Catholicism and her mother, the demonic yarn being revealed by the audio files—none of it comes together into a coherent horror story. And worst of all, nothing happens.

Undertone is an impressive technical achievement but the story’s just not there.